By Laura Carney*

My father met me for lunch at Bennigan’s a few weeks before I made the biggest move of my life—to New York City—in the summer of 2003. It was that lunch with him, and one other, in the same restaurant, five days before he died, that I had to hold onto as I made my way in the big city. Because three months after it, he was gone.

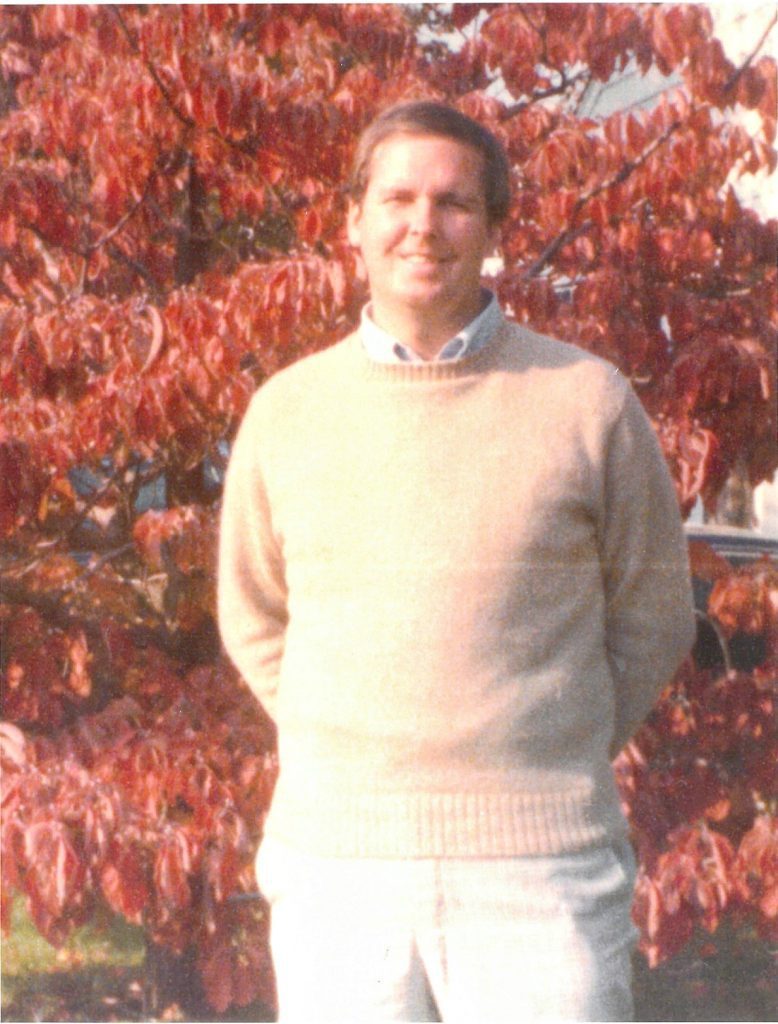

My father worked in advertising and sales for most of his life, but writing was his true gift and passion. He said I was doing what he had always wanted to do, but that he’d settled down in Delaware and gotten married and had kids instead. It always meant so much to me that I shared my father’s passion for the written word—he was my best editor, really. That’s why it is so difficult for me to sum him and his life up in words. And I certainly never thought I’d have to at such a young age.

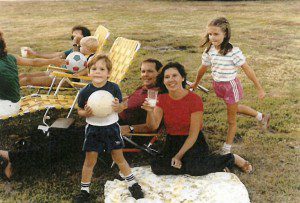

Michael J. Carney (who usually went by “Mick”) was a father, a husband, a brother, a son, an uncle, a cousin and a nephew; a singer, a performer, a poet and a philosopher; an American Studies major at University of Delaware, from which he graduated in 1971, and an avid essayist—he wrote a book called “The Why Generation” in the late 1970s; a comedian and a gifted impressionist; a sentimentalist and lover of literature; an avid sports fan and star high school athlete; a feminist—I attribute much of my self-esteem to the values he gave me; a teacher—in the second half of his life, he substitute-taught in Wilmington-area schools; a born leader, excellent communicator and generous coach—he always instructed my brother and me on the importance of fair play, of expressing yourself clearly and of being comfortable speaking in front of a room; a dreamer—he encouraged anything my brother or I wanted to become…in fact, he was expert at spotting and nurturing our strengths and proclivities before we even knew what they were; a pop culture and trivia aficionado and a man of near-genius—he was like a walking encyclopedia of information both useful and just plain entertaining; a refined appreciator of the arts with impressive taste in films and music; a thinking, sensitive man; a talented and professional salesman; and, perhaps most importantly, a loyal friend. There were so many people who loved him, in fact, that at his funeral I couldn’t keep track of them all. At least half of them I’d never met.

He was always either joking or singing, or telling you something incredibly profound. He had the biggest personality of anyone I’ve ever known, but was generous with his attention. What seemed to matter to him most in the world, at any given time, was that the people around him were comfortable and having fun.

Mick was born on April 6, 1949, in Claymont, Delaware, to Thomas and Mildred Carney, and was one of five brothers. He died at the age of 54 on August 8, 2003, in Limerick, PA.

According to “The Mercury,” a Montgomery County, PA, newspaper, at 1 p.m. that Friday, 17-year-old Bridget McCarthy “ran a red light in her Ford Excursion and crashed into the side of [Mick’s] Mercury Cougar as he was pulling forward to turn left onto Township Line Road.” The crash had several witnesses. A passenger behind my father saw McCarthy run the red light. As she watched my father pull out to make the left turn, the SUV “plowed right into him.” Many witnesses tried to help him, but he was pronounced dead shortly thereafter, according to police. Speed was not an issue. According to “The Mercury,” McCarthy’s Excursion “sustained little more than a small dent, but the Cougar was severely damaged by the impact.”

According to “The Mercury,” a Montgomery County, PA, newspaper, at 1 p.m. that Friday, 17-year-old Bridget McCarthy “ran a red light in her Ford Excursion and crashed into the side of [Mick’s] Mercury Cougar as he was pulling forward to turn left onto Township Line Road.” The crash had several witnesses. A passenger behind my father saw McCarthy run the red light. As she watched my father pull out to make the left turn, the SUV “plowed right into him.” Many witnesses tried to help him, but he was pronounced dead shortly thereafter, according to police. Speed was not an issue. According to “The Mercury,” McCarthy’s Excursion “sustained little more than a small dent, but the Cougar was severely damaged by the impact.”

McCarthy had her 15-year-old sister and 4-year-old brother in the SUV with her, all of whom were not injured. A month later, in court, seven witnesses came in, which the Montgomery County assistant district attorney said was unprecedented in his experience. All of them, the drivers behind my father’s car and the drivers behind McCarthy’s SUV on Route 422, said the light she’d driven through had been red. McCarthy took the stand and said tearfully that the light was red but had changed to green as she approached the intersection. In the end, the judge disagreed, and said there was no doubt in his mind that the light had been red, and she hadn’t seen it. The police officers who’d checked the functioning of the traffic light hadn’t been able to provide sufficient evidence that it might have malfunctioned.

So how could one person see a light as green while seven others (and likely also my father) saw red? Perhaps because that person was distracted by a cell phone.

The headline of the news story about the accident was “Teen Driver in Fatal Crash Cited for Talking on Cell Phone.” She was found guilty that day of running a red light and of careless driving—violations that each carried a $100 fine. Even before the hearing, witnesses had told authorities that they had seen McCarthy on her phone at the time of the crash. In court, McCarthy admitted to holding her cell phone but said she had not been using it at the time, that she’d had both hands on the wheel—her cell phone was in her right hand, she said, but that hand was on the wheel. Apparently, she had gotten lost while driving to a friend’s house and called the friend’s mother for directions after getting off Route 422. In 2003, Pennsylvania had no state law against talking on a cell phone while driving. So there was very little we could do. At the end of the hearing, the district attorney reminded everyone, “Someone died in this accident. The defendant is lucky that more serious charges weren’t filed.”

“Plowed…smashed…slammed…” Those were the words used in the newspaper to describe how my father died. Not words you really want to incorporate with the death of a loved one.

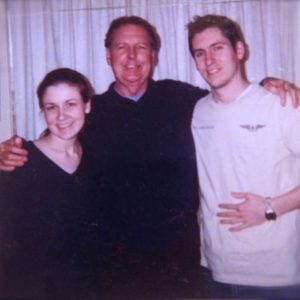

The last time I ever saw my dad was at another Bennigan’s lunch, about five days before the accident. I had come home with my new boyfriend and was excited about introducing him. That day he gave me a very big hug as we left the restaurant. It is an image that will always be in my brain because it was the last time it ever happened. Minutes before that, I’d overheard him telling my new boyfriend, “You seem like a nice young man.”

In that second-to-last Bennigan’s lunch, the one just before I moved to New York, my dad had said something weirdly prescient. He said he remembered how my grandmother used to sit in the middle of the room at holiday functions, holding the youngest child. And he told me he could see me someday doing the same thing.

It was an odd thing to say at the time….And I didn’t know how important this comment would be to me someday, after he was gone. Because he’ll never be there to see me sit in the middle of the room holding a child—my child or anyone else’s. And he won’t be there to see me when I walk down the aisle in May. He won’t be there to give me away to the “nice young man” he met 12 years ago. (It turns out he was right about that.)

The day of my father’s funeral, my brother clasped my hand as we walked down the nave of the church. We gave the only two eulogies. In my heart, I know that he is still guiding me. And I know he would want something to be done to help the victims of distracted driving. He had more to do in his life, when it was cut short. I know he’d want me to reach out to others who had to experience a sudden, senseless-seeming loss like this.

In the years immediately following his death, I worried that this experience was so unique that it would make me seem strange to my peers. I found that they didn’t know how to react when I told them about it. Now, I have very little concern about sharing it, but the reason for that is an unfortunate one—it’s because now I am one of MANY faces of distracted driving.

It is with a great deal of compassion for the victims of distracted driving that I tell my dad’s story. I have so many of these memories of him and life lessons from him that I’m compiling them into a collection of essays. My hope is that by seeing him as a real person, people will understand the true nature of this kind of loss. In addition, I will be running the New York City Marathon later this year in his honor, to raise funds and awareness for EndDD.org. My dad always said I’d be a long-distance runner, and running has been very therapeutic for me in dealing with this loss—I just never knew there was a chance that doing so could save lives. Please visit my page on CrowdRise to help support the cause.

__________________

*Laura Carney is a magazine copy editor and writer based in New York. She has written for Good Housekeeping, the Associated Press, McSweeney’s, Monkeybicycle, Vagabondage Press, various trade magazines, lippsisters.com and fashionandgrammargripes.blogspot.com. She is also running on the EndDD.org team in the Roc-N-Roll Half Marathon in VA Beach sponsored by Travelers Insurance through their “My Drive Comes From” campaign.